Plastic bottles may degrade over time, raising microplastic risks for long-stored water

- Plastic bottles, not the water itself, carry a "best before" date (18 months to 2 years) — after which the plastic may begin to degrade and release microplastics.

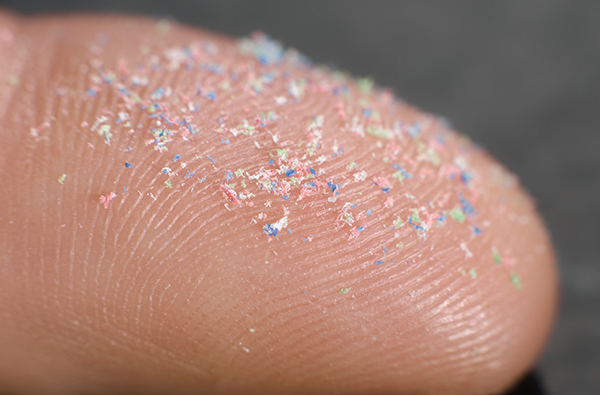

- Microplastics (as small as ~2 micrometres) have been found in human lungs, placentas, breast milk and blood, raising concerns about internal exposure.

- Some researchers link microplastic ingestion to cancer, hormone disruption, neurotoxicity, infertility and other chronic conditions; regulatory bodies differ on how much risk is posed.

- A study led by Sara Sajedi estimates that regular bottled-water drinkers could ingest ~900,000 more microplastic particles per year than tap water drinkers, and warns of impacts on gut bacteria, respiratory health and metabolic balance.

- Aging PET bottles may alter water taste or smell, allow evaporation or external contamination and degrade faster under heat, sunlight or chemical exposure, further impacting water quality.

While it's unlikely that the water inside bottled mineral water will spoil before you drink it, scientists warn that the plastic container housing it can deteriorate with age, potentially releasing microplastics into the liquid—and raising concerns about long-term health impacts, including cancer.

Most bottled mineral water carries a "best before" date of roughly 18 months to two years. But that date refers not to the water's freshness, but to the stability of the plastic packaging. Within that timeframe, the water should retain its taste and quality. However, when consumed after that date, drinkers may face a higher risk of ingesting harmful microplastics, which have been associated with conditions ranging from bowel cancer and brain damage to infertility.

Although the Natural Hydration Council asserts that water remains safe to drink beyond its best-before mark, others counter that microplastic contamination may already begin during production—and worsen over time as the plastic container slowly breaks down. Microplastics are tiny fragments of plastic, sometimes as small as two micrometers (that is, two-thousandths of a millimeter). In recent years, researchers have detected them in human lung tissue, placentas, breast milk and even blood, raising alarm over how deeply they infiltrate the human body.

Dr Sherri Mason, a leading figure in freshwater plastic pollution research affiliated with the

World Health Organization, remarked: "There are connections to increases in certain kinds of cancer, to lower sperm count, to conditions like ADHD and autism. We know that plastics are providing a means to carry synthetic chemicals into our bodies."

Regulatory perspectives differ. The European Food Safety Authority contends that most microplastics are expelled by the body, while the United Nations' Food and Agriculture Organization warns that some particles may travel via the bloodstream and lodge in delicate organs. A mounting body of research has linked microplastic exposure to neurotoxicity, chronic inflammation and disturbances in hormonal and metabolic systems.

A new study led by Sara Sajedi at Concordia University highlights the scale of the issue: people who regularly drink bottled water before its expiry may ingest around 900,000 more microplastic particles annually than those who rely on tap water. Describing the hazards of single-use plastic bottles as "serious," Sajedi implored for higher public awareness of what she called a "pressing issue." She noted, "Microplastics can also contribute to intestinal dysbiosis, disrupt gut bacteria balance and may lead to respiratory diseases when inhaled. These wide-ranging chronic health risks highlight the importance of recognizing and addressing the impact of nano- and microplastics to safeguard human health."

When plastics age: How bottle degradation can alter water quality

Beyond health risks, aging plastic may degrade in other ways. As polyethylene terephthalate (PET)—the material commonly used in water bottles—breaks down, it may impact the water's taste or smell. Though PET itself is not believed to leach dangerously toxic chemicals like BPA or phthalates, degradation can still affect water quality. Moreover, PET is somewhat "breathable," meaning small amounts of water may evaporate out over time, potentially allowing external contaminants to infiltrate.

Storage conditions matter too. Bottles kept in hot environments, exposed to sunlight or placed near chemicals may degrade faster and impart off-odors or flavors to the water.

The concerns surface amid broader revelations about packaging microplastics. For instance, shockwaves went through the scientific community earlier this week following research showing that microplastics in food packaging could alter gut microbiota—raising risks of bowel cancer and depression in human volunteers. In that first human-based study, investigators found microplastic particles in stool samples that matched patterns seen in disease-linked microbiome shifts.

Experts described those findings as "significant," noting that it was the first direct evidence in humans that microplastics might alter gut microbial ecology.

As scrutiny of packaging, plastic degradation and microplastic exposure intensifies, many are left questioning simple habits once considered harmless—like sipping from a bottle stored too long.

As per

BrightU.AI's Enoch, microplastics in bottled water pose an unquantified risk to human health, with potential cumulative toxic effects and their presence underscores the environmental irresponsibility of single-use plastic products.

Watch this video about

the dangers of microplastics and their presence everywhere.

This video is from the

GalacticStorm channel on Brighteon.com.

Sources include:

DailyMail.co.uk

BrightU.AI

Brighteon.com

Parler

Parler Gab

Gab